By David B.

If you’re reading this, you likely have at least some interest in flow-based programming. Maybe you heard about it in passing and are just curious what it is all about. Or maybe you’re really into FBP and you want to know more. In any case, I hope to show that the ideas behind flow-based programming are important and valuable.

For those new to the whole FBP thing, let’s start at the beginning: what is Flow-based programming anyway?

Flow-based programming was invented by J. Paul Morrison (he would say “discovered”). This work began in the 1970s, and systems built with FBP concepts are still running to this day, despite maintenance and upgrades throughout the decades. Maintenance and upgrades performed by people who were not yet born when the program was first built, no less. Not too shabby!

Like many JS people new to the idea, I was first exposed to flow-based programming by way of the NoFlo Kickstarter. Like many others, I buzzed with excitement over a “whole new world” of programming.

Flow-based programming, as defined in Wikipedia, is:

.. a programming paradigm that defines applications as networks of “black box” processes, which exchange data across predefined connections by message passing, where the connections are specified externally to the processes. These black box processes can be reconnected endlessly to form different applications without having to be changed internally… FBP is a particular form of dataflow programming based on bounded buffers, information packets with defined lifetimes, named ports, and separate definition of connections.

Again, like many others, I eventually walked away confused. I left, scratching my head, wondering what it’s all about. But Flow-based programming (FBP) lingered in my thoughts long after the initial excitement wore off.

Well, I’ve had time to think about it, and it is my hope that this article will shine some additional light on what FBP is, and what benefits I believe it offers. Along the way, I will demo part of a simple Javascript ToDo app built using a tiny flow-based programming framework I wrote called rhei.js.

Let’s take a look at some of those benefits I mentioned.

Parallelism

Anyone who has browsed through the Google Group will undoubtedly come across JPM himself, reminding us that NoFlo and many others are not “classical” FBP. Read more here. To my understanding, “non-classical” FBP differs from classical FBP in several ways, but one of the major differences is that classical FBP allows for real parallelism (as opposed to concurrency).

I have not yet reached the mastery to judge whether this is a deal-breaking limitation. Parallelism certainly provides performance benefits in some situations, but with modern concurrency scheduling, I’m not certain this is a critical complaint.

In any case, I think that even if you ignore Web Workers, as most of us seem to do, Javascript will likely be parallelizable in the (near?) future. See SIMD.

To illustrate why parallelism is beneficial, imagine a particular piece of code that is processing a large amount of data, and has become a bottleneck. In the flow-based programming world, we can simply copy that component and let it run in parallel, thus “cooling down” the hotspot, with very little modification to the program.

Async

If you will indulge me for a moment, please have a quick look at the story of async Javascript.

In the beginning, we had callbacks:

doIO(function (err) {

if (err) return;

// do some stuff, get a result

doOtherIO(function (err, result) {

if (err) return;

// do some other stuff, get another result

return result2;

});

});… wherein we simply passed functions to other functions to be executed at a later time, usually after an IO operation. To re-iterate the problems we’ve had with callbacks is to beat the pulpy remains of an already-beaten dead horse. Needless to say, the people cried for better async. So lo and behold, promises arrived:

doIO()

.then(function (x) {

// this is still a callback

return something;

})

.then(function (y) {

// this is still a callback

return somethingElse;

})… which certainly look a bit nicer than the callback hell trees we dealt with in the early days. But if there is any branching (error handling, etc), then what do you really gain? We still have a tendency to spread it out like the pyramid of doom situation above, because we haven’t really gotten away from callbacks, we’ve just adjusted how they look.

What about FBP? Well, easy async is one of my favorite aspects of flow-based programming, because FBP is all async, all the time. You just don’t have to think about it. A component will execute when there is some data for it to work on… that’s it. Whether you are waiting for an ajax response or input from the user, or a long computation, all FBP components are independent of one another. This lends FBP components to easy parallelism, as I mentioned above.

Externally Defined Connections

Promise chaining like the above often reminds me of the command-line. If you’ve ever done ps aux | grep node then you’ve gotten a taste of flow-based programming. In the command-line, we use very simple programs that are completely ignorant of each other. We connect them with “pipes”, taking the output flow of one program, and feeding it into the input of another.

The command-line espouses a type of “pipeline” programming, where there is no branching possible. Rather, branching in pipeline programming is possible, but not incredibly easy or sane to do. You might think of flow-based programming as an enhanced and expanded pipeline programming.

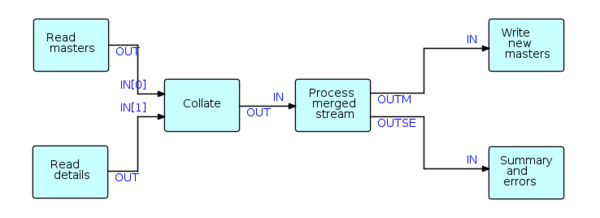

Let’s take a look at an FBP program:

For those completely new to flow-based programming, the diagram above IS the program, just as ls -la | awk -f report is a program. So of course Read masters and Collate are “normal” programs containing “normal” code, just as ls and awk are themselves programs. We’ll always have to write code. But just as you don’t have to worry about how ls is implemented, or even what language it is written in, FBP modules like Collate are also meant to be just as plug and play.

As an aside, flow-based programming lends itself to the microservices architecture. Just as the microservices architecture doesn’t care about how each component is written, FBP only worries about the connections between components.

In fact, there exist flow-based programming networks running in the wild where some FBP components were written in Java, and others in C++. And since async is no obstacle, it might be possible for a FBP network to consist of some Haskell components living in Berlin, some APL components in Rio De Janeiro, all waiting for data from a python component in NYC.

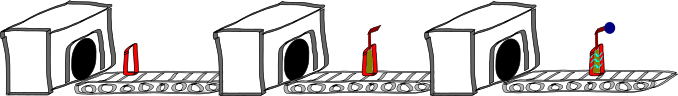

Conveyor belt, or plug n’ play programming

One way to think about flow-based programming is to consider “code flow” vs “data flow”. When hunting bugs or modifying programs, we often think about “where the program is” or “what is executing?”. With flow-based programming however, we are following the data (the “information packets”, in FBP jargon) through the system. We follow parts on a factory floor. We ask ourselves “where is the data?”, and “what does the data look like right now?”. Similar to electrical signals in an electronic circuit, we can probe the data at a connection for debugging purposes. We can similarly track a single datum through the factory machines that we have connected together.

FBP is the conveyor belt that connects the various factory machines.

This style of plug-and-play, or “Lego” programming, is often looked upon with skepticism, probably due to the wide array of graphical programming environments aimed at children, such as Scratch. But even with a cursory glance, you will find flow-based programming bears no resemblance to these projects. Rest assured, flow-based programming is powerful and scalable enough for real-world applications.

Flow-based programming is sometimes called a “coordination” language. It is not really concerned with programming “in the small”, but rather the architecture “in the large”. It separates these two skills. It allows the architect/programmer to coordinate components into entire systems. The designer of the larger FBP network might never write a single component. Similarly, component authors might never know or care about the network their module is meant for.

An added benefit of this separation of work is that it forces one to do real architecture design first, instead of jumping in and hacking on code as a first step.

Let’s try it

Okay, enough theory, let’s get our hands dirty. There are several choices out there for pre-built FBP-like solutions. There’s IBM’s NodeRed, and there’s Blockie.io, both of which seem to be focused on the Internet of Things. There are also projects like Meemoo and Visor Create both of which seem to be focused on media creation.

But I’d like to start as general-purpose and as simple as possible, so how about NoFlo? Well… it’s pretty big. It has a lot of stuff. CoffeeScript, node.js, grunt, a special graphical UI. Can’t I just try this out in a browser console with a skeleton html? Can we go simpler?

For the purposes of this article, I decided to implement my own tiny FBP-like framework: rhei.js. I won’t go into the details of the framework in this article, but in using it, I’ll try to demonstrate why I think the ideas behind FBP deserve our attention.

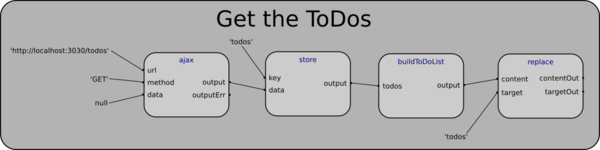

So let’s look at how we might get the list of ToDos with a simple ajax server call, store the list in localStorage, build the html, and render it to the page:

What’s going on here? ajax should be self-explanatory. store simply stores incoming data into the provided key in localStorage. buildToDoList just takes the array of ToDos provided by server (and passed through store), and builds the html for the list. replace takes a DOM id and some html and replaces the content of the target with the html.

Each component is completely ignorant of any other component, has no internal state, is simple to unit test, and when prototyping, can be replaced with a component that just outputs dummy data.

You might ask yourself how this is different from just following good functional programming or SOLID practices. I certainly did. So let’s try to implement the above in plain Javascript. Assuming we have monads/promises, we might write this as:

function ajax (url, method, data) {

// do ajax stuff

return promiseOfResult;

}

function buildToDoList (todos) {

// construct html

return html;

}

function replace (content, target) {

var t = document.getElementById(target);

t.innerHTML = content;

}

ajax('http://localhost:3030/todos', 'GET', null)

.then(store)

.then(buildToDoList)

.then(replace)

.catch(catchErrBecauseImAGoodBoy);

Nice. But as I foreshadowed, what if there is branching logic? What would that look like? As a completely contrived example, let’s say on error, the server sends a url in case the client wants a detailed explanation. We want to take that url, make another ajax call, store the error in localStorage, and render it to the DOM.

ajax('http://localhost:3030/todos', 'GET', null)

.then(function (result) {

if (result.status < 400) {

return promise()

.then(store)

.then(buildToDoList)

.then(replace);

.catch(catchErrBecauseImAGoodBoy);

} else {

return ajax(result.newUrl, 'GET', null)

.then(storeErr)

.then(replace);

.catch(catchErrBecauseImAGoodBoy);

}

})

.catch(catchErrBecauseImAGoodBoy);Admittedly this is not the worst-looking thing ever, but it’s not as clear to read as the non-branching example, and you can see how this can grow into a mess very quickly. Just for “fun”, let’s try just using old-school callbacks:

// jQuery because why not

$.ajax({

method: 'GET',

url: 'http://localhost:3030/todos',

success: function (err, todos) {

store('todos', todos);

var html = buildTodoList(todos);

replace('todos', html);

},

error: function (newUrl) {

$.ajax({

method: 'GET',

url: newUrl,

success: function (explanation) {

storeErr('errors', explanation);

replace('testError', explanation);

}

});

}

});Yikes. The fundamental problem here as I see it, is that text is essentially a 1-dimensional array of characters. This is great for computers, but not the best way to represent large, branching systems. Branching by definition stretches and expands. But with text, we are forced to represent branching linearly: if (this) { do this } else { do this instead }. But with flow-based programming, the program can be represented as a 2 dimensional graph, which can illustrate branching in a very natural manner. If you have a good graph editor, you can quickly “zoom out” to get a bigger picture of the program, or “zoom in” to get a closer look at the components.

True, you can zoom out of text too, but is this:

… really that useful? Someone who is very familiar with the code may glean some minor insight, but anyone new to the code would find the zoomed-out text useless.

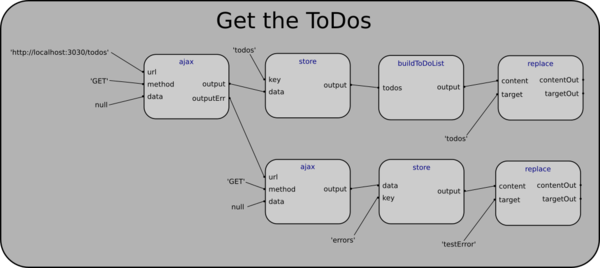

Well then, what does branching in FBP (or at least my simple version of FBP) look like?

If you are a human being with no programming experience, the graph above should be more navigable than the code preceding it. Why? Because humans possess what is known as spatial memory. It is a built-in optimized processing unit in your brain for making your way around spatially-oriented information.

If you are a programmer, you could be very familiar with textual code like the above, and completely unfamiliar with graphical representations of programs. And so you might feel more comfortable with code. But I posit that this is an illusion dictated by your years of experience with text-based coding. If you spent half as much time programming in FBP style, you’d be just as if not more comfortable with the graph.

This isn’t to say that we must program graphically when doing flow-based programming. In fact, using rhei.js, I do not yet have a graphical editing solution, so I textually define the network above like this:

FBP.network({

name: 'ajax',

processes: [

{name: 'ajax', component: 'ajax'},

{name: 'ajaxErr', component: 'ajax'},

{name: 'storeTodos', component: 'store'},

{name: 'storeErr', component: 'store'},

{name: 'buildToDoList', component: 'buildToDoList'},

{name: 'updateDOM', component: 'replace'},

{name: 'updateDOMErr', component: 'replace'}

],

connections: {

'ajax.output': 'storeTodos.data',

'storeTodos.output': 'buildToDoList.todos',

'buildToDoList.output': 'updateDOM.content',

// error branch

'ajax.outputErr': 'ajaxErr.url',

'ajaxErr.output': 'storeErr.data',

'storeErr.output': 'updateDOMErr.content'

}

});One could use a graph editor to do the same thing, as all we are doing is listing the processes to use (the active components), and their connections. Then actually running the network (with the parameters shown in the graph), is done by:

FBP.go(

'ajax',

{

'ajax.url': 'http://localhost:3030/todos',

'ajax.method': 'GET',

'ajax.data': null,

'ajaxErr.method': 'GET',

'ajaxErr.data': null,

'storeTodos.key': 'todos',

'storeErr.key': 'errors',

'updateDOM.target': 'todos',

'updateDOMErr.target': 'testError'

}

);Despite building the graph textually instead of using a graph editor, modifying the program for the contrived branching flow required the same work: adding nodes to the graph, connecting some edges, and providing parameters. No new code was written, as I reused the existing components.

The End

I hope you’ve enjoyed this little foray into flow-based programming. While FBP is certainly useful, and fun to create programs with, and has many advantages over textual programming, I think the real lesson to be learned here is: “how should we think about our programs?” Can we write functions/modules that can be viewed as “black boxes”? Sure. Can we write them in such a way that they can be infinitely reconfigurable, connected externally? Yep. Can we model our programs on factory machines and conveyor-belts, focusing on data? Yes! When we do, we gain many of the benefits of flow-based programming.

And I think that’s worth at least thinking about.

Links

If this FBP stuff interests you, here are some links you might enjoy:

PyF – “A python open source framework and platform dedicated to large data processing, mining, transforming, reporting and more.”

JavaFBP – “Java Implementation of Flow-Based Programming (FBP)”

Straw – “Straw lets you run a Topology of worker Nodes that consume, process, generate and emit messages.”

IFTTT – “Gives you creative control over the products and apps you love.”

Elixer – “An Elixir implementation of Flow-based Programming”

LabView – “A development environment designed specifically to accelerate the productivity of engineers and scientists.”

JsMaker – “Visual Javascript Programing”

Reading suggestions

Dataflow and Reactive Programming Systems by Matt Carkci

And of course nothing beats reading the book that started it all: Flow-Based Programming, 2nd Edition: A New Approach to Application Development by J. Paul Morrison. You can read the first edition online here.

Note on rhei.js

rhei.js is just a toy. It does not follow many of the FBP tenets such as: strict IP lifetimes, or bounded buffers, or substreams / brackets, or error handling, or composite components, or or or… in other words do not use rhei.js for anything. If you do feel like playing around with this toy, note that it uses ES6 arrow functions. So use node –harmony app.js for the server, and use Firefox for the client.